After almost three years and many ups and downs, Verena Liedgens decided to close the doors of her social business. One of the main lessons she learned was that sometimes a strong value proposition is still not enough. While a value proposition may be perfect in theory, it’s crucial to learn how to test the roles that culture and idiosyncrasies play in its actual rollout. Here she takes a closer look at the Agruppa case-study and what she learned along the way.

Agruppa had a very clear value proposition from the start: Mom-and-Pop shops using our service would save money and have an easier life. Without Agruppa, shop owners travel to the central market of the city almost every day, getting up at 3 or 4am in order to go shopping and be back at their store around 7am to welcome the first customers. This is not only a huge time investment, but also costs them over $50 USD per week. In addition, it is a security issue and a plain headache (who likes to get up at 3am every day? Exactly.)

Agruppa’s mission was to change this inefficient practice, to save shop owners time and money, and to make their life easier by delivering the produce directly to their shops (more detail on our business model here).

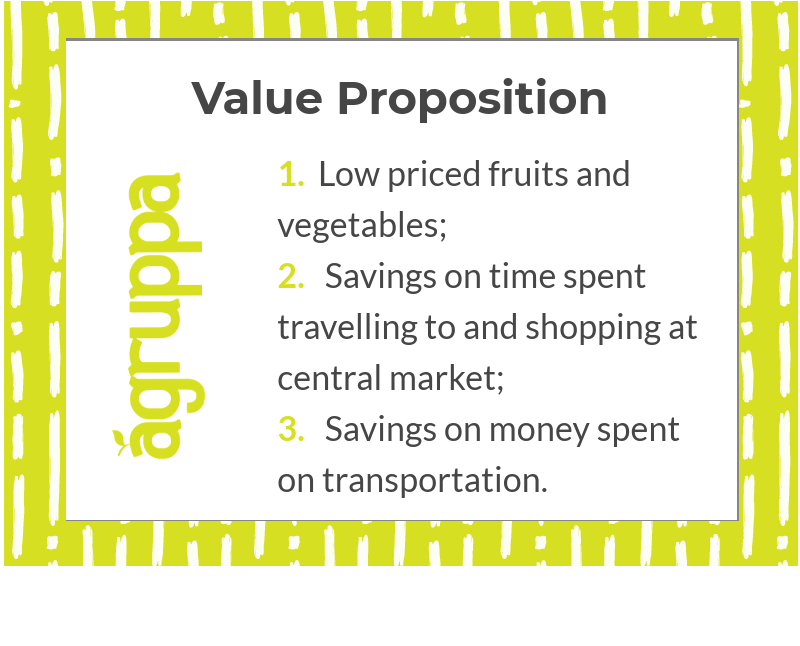

So the value proposition, our promise, to the Mom-and-Pop shops was threefold:

Sounds like a no-brainer? That’s what we thought. And we had not just come up with this value proposition, but engaged in extensive market research before even starting our first pilot, spending countless hours interviewing and engaging with shop owners, as well as tracking market prices, interviewing farmers and understanding the value chain. And indeed: basically every shop owner we talked to confirmed the heavy load that their shopping practice represented, and showed strong interest in receiving lower priced produce straight from the farm (and sleeping longer).

Sounds like a no-brainer? That’s what we thought. And we had not just come up with this value proposition, but engaged in extensive market research before even starting our first pilot, spending countless hours interviewing and engaging with shop owners, as well as tracking market prices, interviewing farmers and understanding the value chain. And indeed: basically every shop owner we talked to confirmed the heavy load that their shopping practice represented, and showed strong interest in receiving lower priced produce straight from the farm (and sleeping longer).

From day one of our operations, however, we struggled to retain customers. It’s not that the idea did not sound promising to them. But we were just not good at delivering it. We struggled with product quality, delivery times and pricing. We were just not good at it yet, or so we thought, and so we just kept working harder, trying to get there.

Seven month into our operations, we were lucky enough to launch a rigorous study to measure Agruppa’s social impact, funded by the World Bank. Our metrics were (with some specifications) exactly the same as our value proposition. The same three reasons why a shop owner should buy from Agruppa were how we were going to impact their life positively. This congruence is typical for social enterprises that develop services for the poor that they themselves pay for.

While the final results of this study are not yet public, the preliminary results from a midline survey after six months were incredibly encouraging: Mom-and-Pop shops buying from Agruppa on average saw a 10% price decrease in staple fruits and vegetables and cut the money spent on transport in half. Adding these savings together, they represented approximately six Colombian minimum salaries per year. This was more than we had ever imagined to be able to deliver to our customers.

We were stoked. Unfortunately, our customers were not. While we had build a very loyal customer base one the one hand, on the other we were struggling with retention and losing a lot of shops after just a couple of purchases. Others would be constant and returning customers, but much more sporadic than expected. And only very few were buying the ticket size we were conservatively expecting, based on data they themselves had reported to us. We knew we continued to not deliver exactly what we were promising, or at least not every day.

And then, we learned that transporters that used to deliver produce for Agruppa to Mom-and-Pop shops continued to serve these shops on their own initiative after we had let them go. The crisis was real, . Even if there was obviously a demand for the Agruppa service, we could no longer figure out what our true differentiator was. If a random truck driver that we had hired, trained and shown the opportunity could do it by himself, what the heck were we still doing? Why were we still burning through a lot of money while watching him do exactly the same thing?

Even after crunching our sales data, speaking to customer-facing staff, we could not see clearly among this sea of truly encouraging feedback and numbers that were not matching up. During that time, we were lucky enough to receive pro-bono support from Mighty Ally. Kathleen, a founder of the strategy consultancy for changemakers, came to Bogota to join us in deciphering what was going on, and helping us get back on track with our values, our mission and the value we could truly add to the small shops we so desperately tried to support.

In only a week’s time, Mighty Ally x-rayed Agruppa and took us back to basics: to engaging with our customers. We went back to customer discovery — to semi-structured interviews aiming at revealing what matters most to Mom-and-Pop shops, what their pain points and their most precious values are. It was eye-opening. While we had always been in touch with our customers, since starting operations we had not gone back to talking to them outside a sales interaction. As a result we had also never engaged closely with Mom-and-Pop shops who had stopped ordering from Agruppa. This time around, we spoke to all of them: loyal ones, sporadic ones, drop-outs; the happy ones, the angry and annoyed ones. With the support of Mighty Ally, we consolidated all these conversations into one major finding: the Mom-and-Pop shop market that we had tackled could be divided into two very distinct customer segments: the Sofias and the Oscars.

Shopbound Sofias are shop owners who have a strong practical reason not to want to leave their shop and go to the central market. They may be caring for children or elderly, becoming older and tired themselves or be concerned about their security. Whatever the reason, they really do not want to make that trip. Hence, they strongly value the direct delivery to their shop and often become very loyal Agruppa customers.

Occasional Oscars, on the other hand, only buy from Agruppa occasionally. They use Agruppa for the sporadic need that does not justify a trip to the market, or to stock up on certain products between trips. But Oscars would never drop their habit of going to the central market. To the contrary, it is central to their identity as a shop owner, their social life or their ego, and the feeling of having selected and negotiated produce themselves becomes primary to everything else.

Don Alonso — a street vendor and Sofia-type customer of Agruppa

It turned out that Sofias had much smaller shops than Oscars, and since Oscars only ordered with Agruppa sporadically, their ticket sizes were just as small (or even smaller). According to our own estimation, Oscars made up about 80% of our accessible market, and Sofias only 20%. Since these two market segments have distinct needs and motivations that attracted them to Agruppa, it is impossible to serve both well at the same time (and it became blatantly obvious that this was what had made us bang our head against the wall for months). The Sofias did not represent a big enough market opportunity for Agruppa, and for the occasional Oscars, we did not have a bullet proof value proposition.

Unfortunately, we did not have sufficient runway to figure it out — to pivot into a service that would (a) be more attractive for Oscars, or (b) make more money off Sofias. This dilemma ultimately lead to the closing down of Agruppa. While Mighty Ally could not turn around the sinking ship, their engagement with Agruppa (which went way beyond this customer discovery) was incredible valuable for us, and a true eye opener.

What remains are two main lessons:

-

While what Agruppa offered was meaningful to the whole market, there were other things that for certain groups were more meaningful. So only because your value proposition is attractive to your target customers, that does not automatically mean it will actually convert and — most importantly — retain them. This explains what had always seemed like the biggest irony: while our social impact on customers was supported through the World Bank study, they “just did not see it”.

-

When building and scaling an enterprise, it is absolutely crucial to make customer discovery an ongoing practice. While many companies have built great feedback loops with their customers (which is important), this is different. It is indispensable to engage with current, future and ex-customers outside of sales situations, to really understand what drives their decisions every day.

These lessons came too late on our learning journey. We hope that maybe they’re just on time for others.

This article is part of a series by Verena Liedgens which aims to share lessons learned from a social business practitioner - with hopes of enlightening other entrepreneurs facing similar challenges. Liedgens describes herself as: "A social entrepreneur without an enterprise. Co-Founder of Agruppa. Passionate about food, business model innovation and using markets for a more inclusive future."